At the Forefront of the Rearguard

A documentary film by Alex Gribenes

As everybody knows, we live in an age of science. As everybody sometimes doesn’t know, we also live in an age of anti-science.

That is, everybody sometimes doesn’t know it until now. Alex Gribenes’s new documentary about the Texas State Anti-Science Fair of 2015, At the Forefront of the Rearguard, is a must-see, and makes the reality of our anti-scientific age something everybody will soon know whether they know it or not.

What is anti-science? It is the rigidly-systematized, peer-reviewed, amply documented discipline that proves that science is hooey. But the anti-scientist does more than develop theories about the physical world.

She (or he) promotes a world-view, too—namely, that scientists are, really, when you think about it, basically a bunch of frauds. If anti-science is true, then science is false — which means that scientists are phonies and hoaxers who, in the tens of thousands, throughout history and all over the world, have conspired to promulgate baloney “theories” and conduct faked “research” merely to obtain grant money and get tenure in universities. Then they go on TV and build big fancy machines that don’t prove anything in order to win the Nobel Prize so they can go to Sweden and eat shrimp cocktails and drink champagne.

As explained by a high school anti-science teacher in the documentary, anti-science owes its success to the anti-scientific method, a strictly-determined protocol of inquiry by which the real explanation for everything is to be found in the Bible. For centuries, the anti-scientific method has proven durable and air-tight in its consistency.

Anti-scientists know that God said and did certain things, because they’re in the Bible. They know the Bible is true, because it’s the word of God. Why else would we swear on it in court? Thus does the anti-scientific method yield the inarguable, unchallengeable axiom, “The Bible is true because everything that it says is in the Bible.”

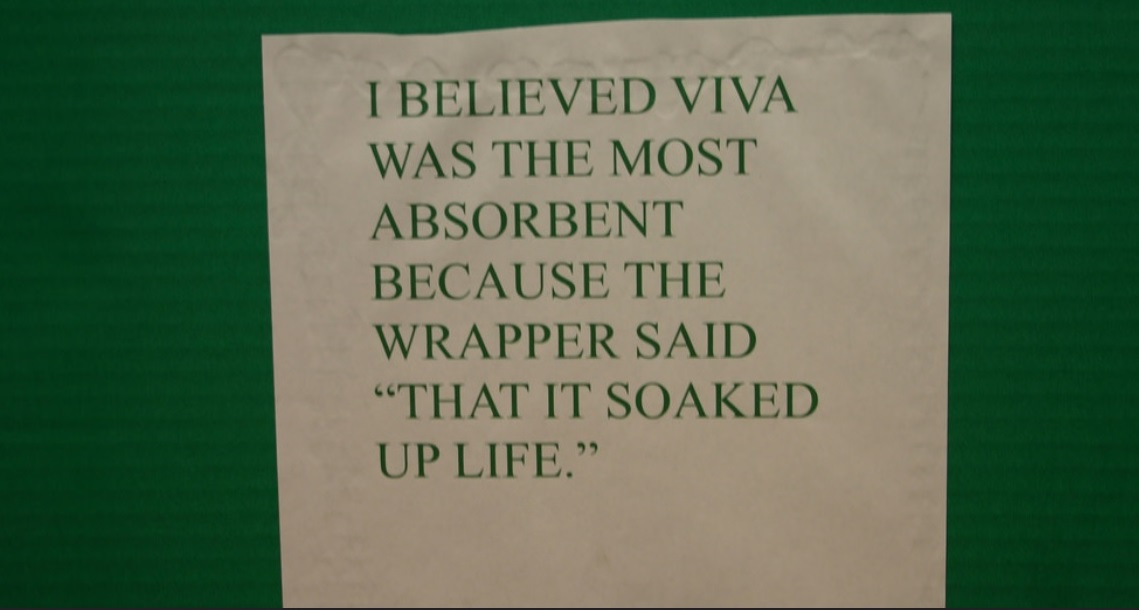

The spirit that animates anti-science inquiry — of curiosity, followed by brief uncertainty, followed by conclusive proof, followed by triumphantly renewed certainty — is captured in Gribenes’ documentary. The film focuses on three Texas students: John Caldwell, a 7th grader; Amy VanDerPlatz, a 10th grader; and Steven VanDerCaldwell, a high school senior. The director was given carte blanche access to the three students and their families over the course of the six months the young people worked on their anti-science projects, with all three “story-lines” converging dramatically at the Texas State Anti-Science Fair, held in March, 2015 in Houston.

Both the high points and the low points of anti-scientific research are well-documented in the film —perhaps, in some cases, too well-documented. We spend six full minutes watching anti-botanist John Caldwell kneeling in silent supplication over a snake plant for his entry in the Botany category, “Influence of Prayer and Scriptural Recitation on the Growth of Sansevieria trifasciata.” It’s a first-hand glimpse of the dedication and patience required of any anti-scientist, but might not a single minute have made the point more concisely?

Then again, John emerged the first-prize winner in the Middle School competition. (Both the plant he prayed over, and the one he read Bible verses to, grew nearly an inch taller than the control group, which he left outside and sometimes forgot to water.) So perhaps it was Gribenes’s intention to make us feel, and not merely witness, the kind of tedium anti-science demands of its acolytes.

Amy’s entry begins with an enigmatic sequence—a Christmas vacation trip with her family, from their home in Dallas, to her aunt’s and uncle’s home in Millner, Kansas. Only once there do we realize that this 16-year-old anti-meteorologist is engaged in field research. It rarely snows in Dallas, of course, but in Kansas the drifts are two feet deep, allowing Amy to conduct her research by repeatedly throwing snowballs at a Stop sign for her experiment, “Effect of Projecting Impacted Spheres of Crystalline Water Ice at Municipal Signage to Demonstrate Fraudulence of Claims of Global Warming.”

As she poses on her display, in everyday language for the benefit of the lay person, “If the Earth is getting so hot, how come it still snows everywhere?” That she wins an Honorable Mention is proof positive that anti-science can be fun as well as intellectually rewarding.

Steven VanDerCaldwell’s entry in the Physics and Astronomy category represents a triumph of ingenuity over practical limitations. How do you obtain footage of an event that happened 6,000 years ago? You can’t. So the young anti-cosmologist performs a neat bit of conceptual jiu-jitsu, using the findings of science to prove his anti-scientific point in his first-prize-winning exhibit, “Let There Be Light: How Do Compilations of Descriptions of the Big Bang in Magazines and on Web Sites Prove the Book of Genesis Has Been Right All Along?”

Although they’re not brought to us in as much depth, we are afforded glimpses of other anti-science projects covering a wide range of specialties, including Geology (“Refutation of Carbon-14 Dating via Demonstration of Absence of Its Mention in the Old and New Testament”), Mammalian Biology (“Using Photos of Apes Taken at the Zoo In November to Disprove the Theory of Evolution”), and Physiology and Medicine (“Complicatedness of Eyeball Structure Which No One in History Has Ever Invented as Proof of Intelligent Design”).

The achievements of anti-science are impressive by any measure. That human beings have, for thousands of years, been capable of beating back the forces of materialism and objective fact by the dogged application of doctrine and faith, has brought new meaning to the word “miracle.” Gribenes’s lively account of these young anti-scientists demonstrates that that tradition remains in good, clasped hands.