ADAPTATION ADEPTS: How Nature Has Learned to Survive in a Changing World by Al G. Bloom (Rando House; 375 pp. w/ photographs; $29.95.)

That animals—and, indeed, plants and all living organisms—propagate their species by adapting to changing environmental conditions, is hardly news. We call it “natural selection,” and its mechanism has been understood at least since 1859, when Charles Darwin published The Origin of Species.

In the ensuing century and a half, scientists and lay people alike have marveled at the complex, ingenious, and often astounding ways creatures have developed to survive changes in their environments, adjusting to and prevailing over alterations in predator behavior, weather and climate, forage and prey availability, and competition for resources.

Some of the most remarkable of these adaptations are now brought together in a volume by Al G. Bloom, Professor of Evolutionary Science at the University of Mischegoss at Ypsilanti-on-Oopsie-Daisy. Bloom’s lucid text, together with an array of stunning photographs, provide an eye-opening account of some of Nature’s cleverest survival schemes.

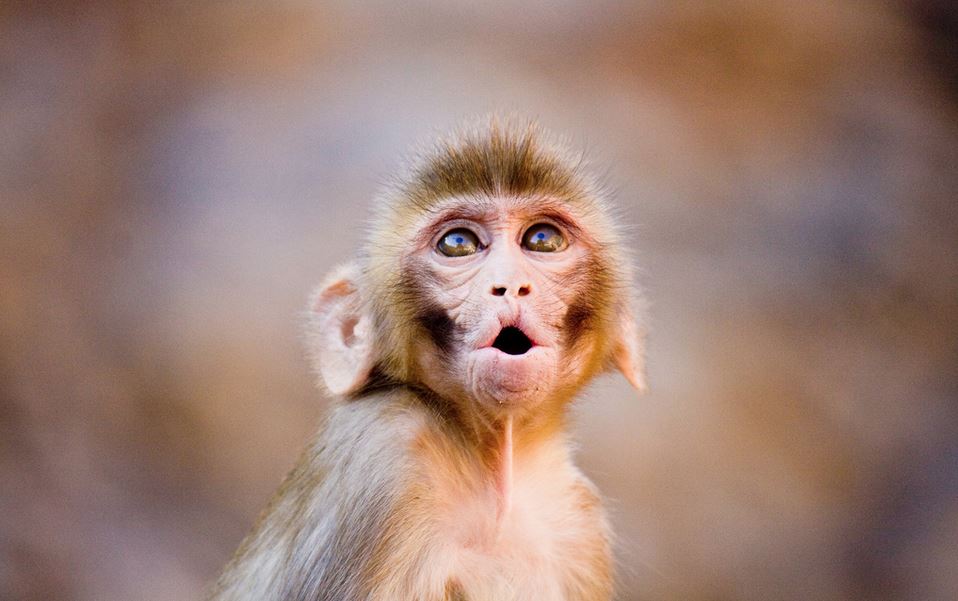

For example, the male salted nut-hatch has learned, over the years since its first migration to the continent of Australia, to mimic the call of the male tom swift, the better to lure into proximity the female swift for recreational fraternizing. Other examples of cross-species mimicry include the moptopped beetle, which has learned to annoy its sister by making fun of the way she chirps, and the rhesus-pesus monkey of Indonesia, which is able, not only to mimic other primates in its rainforest habitat, but to do a creditable impression of Antonio Banderas, Woody Allen, and Cher.

Naturally the encroachment of human civilization has had a profound effect on many species, and none more so than on the hiho silver salmon, in the American Pacific Northwest. This fish has, over generations, acquired the ability to apply to community colleges, major in Communications Arts, and take various “gigs” including web management, content creation, and developmental editing. As a result, it has found a way, not only to successfully evade its natural predator, which is humanity, but to work constructively with it on a variety of exciting start-up ventures.

However, not all adaptations can be said to work out for the better. Professor Bloom takes note of the case of the Kodak bear, native to Alaska and Western Canada. This hardy ursine species spent generations learning and mastering the ability to photograph itself, both in “candid” shots and in poses with tourists, with both the Brownie Hawkeye box camera and even with later, more advanced disposable cameras.

However, the advent of digital photography, and its ubiquity as a feature of touch-sensitive cell phones, proved too demanding for the animal’s large paws. The Kodak today faces extinction, or at best a narrowly limited niche role shooting catalogue and periodical spreads—and those, alas, in the somewhat limited circumstances in which the shot—of a bikini-clad model or a businessman in a suit–requires a bear.

In sum, Adaptation Adepts is an excellent work, one that repays idle browsing as well as methodical study. Whether discussing creatures of the land (e.g., the Amazon firestick ant, which has evolved an ability to “stream” “content” from “the web”), the sea (Jackson’s pollock, a fish that has learned to swim madly about in random patterns until its prey doesn’t know what to think), or the air (the patriotic bunting, which has learned to conceal its essential bigotry behind a colorful display of red, white, and blue), this volume has something for anyone interested in nature’s strategies for assuring survival in a dangerous and changing and insane and, really, kind of fucked up world.

Garrett Ziegler

http://tinyurl.com/p7mmo9f