Henry Doupea

By Maurice Clod; translated by the author

Gallimaufry, 312 pp; $23.95

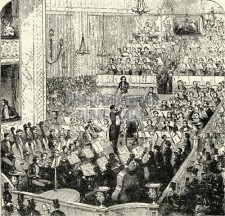

March 14, 2008: A tense silence fills the tiny concert hall of the Snitley (Mich.) Symphony Orchestra and Storm Door Company. “Concerto In F Major For Accordion Vs. Brass”, a recently discovered major work by Henri Doupier (1824-1867-1882), has just received its American premiere. The eerie hush lasts for almost two minutes before the muffled retching of a Lansing music critic breaks the spell. This sets off three hours of chair-throwing, the spread of hysteria to the village square, and a night of looting, arson and vandalism which levels the town by morning, leaving only the smoldering ashes of a flugelhorn to mark the site of the performance.

Bizarre? Yes. But the career of Henri Doupier, 19th-century French Repulsivist, was anything but commonplace. This man, composer of over 12,000 uninspired works (including nearly 4800 annoying symphonies), generated negligible excitement in his own time and failed to influence the course of music for centuries, even decades, after his death. Now, thanks to the bafflingly prodigious efforts of Maurice Clod, Doupier’s story is told in “Henry Doupea”. (Clod’s misspelling of his subject’s name is, admittedly, a flaw.)

Henri Marie Axelrod Doupier was the son of the Franco-American Indian artist Sky-Heavy-With-Rain Doupier, whose “Woman Juggling Beaver Pelt” hangs to this day in a lavatory just six blocks from the Louvre. As a child, Doupier suffered greatly at the hands of his father, who repeatedly dropped him down steep flights of stairs.[1]

Henri Marie Axelrod Doupier was the son of the Franco-American Indian artist Sky-Heavy-With-Rain Doupier, whose “Woman Juggling Beaver Pelt” hangs to this day in a lavatory just six blocks from the Louvre. As a child, Doupier suffered greatly at the hands of his father, who repeatedly dropped him down steep flights of stairs.[1]

Then came the years of heartbreak in the squalid Parisian gutter where he composed his life-work. Remarkably, Doupier produced up to sixty pieces of music a day, primarily by keeping all symphonies and operas under ten minutes in length. “No one can stay awake for more than one movement of any symphony,” he said at one time.[2]

For many years, Doupier’s efforts were totally ignored. Finally, in 1858, things got worse: a small ensemble in Bordeaux agreed to present the world premiere of “Song Without Music”. When the conductor lowered his baton to end the twenty-eight minutes of silence, the audience stumbled confusedly into the aisles and probably was responsible for the run on hearing aids in Bordeaux the next day.

But the most inspiring moment of the evening was yet to come. In his box overlooking the departing crowd, Doupier slowly rose and lifted both arms above his head, indicating the Deity.[3] The magic of this moment is somewhat dimmed, however, by the subsequent revelation that Doupier was being robbed at the time.

The story of his pitiable decline can still bring tears to the hardest-hearted amongst us.[4] His 1863 mariage to the notorious orthodontist Frances “Killer” Gruyere ended after one tempestuous year when she gave birth to a child who she admitted wasn’t related to either of them. Doupier’s attention seemed to flag and his experiments with form, such as the appearance of brief cockfights during the later sonatas, are today dismissed as the acts of an obvious madman although they were less well-received at the time. His friends were shocked and dismayed by his decision to have cosmetic heart surgery. Then came the rapid drop into oblivion as Doupier renounced music altogether and spent the last years of his life attempting to breed racing cows.

Yet there is so much we do not know. Where was Doupier during “The Lost Years” (18??-18??)? Why did he register as “Mr. and Mrs. Jean Smithe” at Une Heure Joyeux Motel that night in 1868? And what did he mean when he wrote in his journal: “Some day, young women will wear huge heels on their shoes while dancing. This will be my vindication!!!”[5]

No one knows. Fewer care. Until Clod, Doupieriana was appropriately scarce. The otherwise excellent biography, Doupier: Myth Or Man? by Lesley Gore (Lovergirl Press), ultimately fails to answer the crucial questions. Frankie Valli comes closer in Babe Of Brilliance (Tangential), his intensive study of the first sixteen hours of Doupier’s life.

But in the end we have only his music to help us solve the riddle that is Henri Doupier. Unknown in his own time, forgotten today, Doupier remains more-or-less transcendent, a shadowy figure lurking behind the curtains of history, waiting silently in the dark until his unsuspecting prey (perhaps Civilization itself) looks up from the writing desk to feel the gnarled hands wrapped around his, or its—no, make it his–neck.

[1] In an 1861 letter to Philippe Jejune, the jazz economist, Doupier remarked “Those stairs made me what I am today. Or, y’know, not.”

[2] “Take your filthy hands off me!” he said at another.

[3] Doupier gave credit for all his musical gifts to God, who repeatedly denied knowing him.

[4] Hyram Bent, 252 Bristol Rd., San Luis Obispo, Maine.

[5] Lionel Fitzbibby, Prof. of Music at Lookoutbehindyou State University, notes that “Although Doupier wrote only one exclamation point here, he obviously meant to have three…” See Fitzbibby, “Exclamatory Phrases In Doupier’s Journal: How and Why???”, Review of Irrelevant Esoterica (March, 2003), pp. 1051-1102